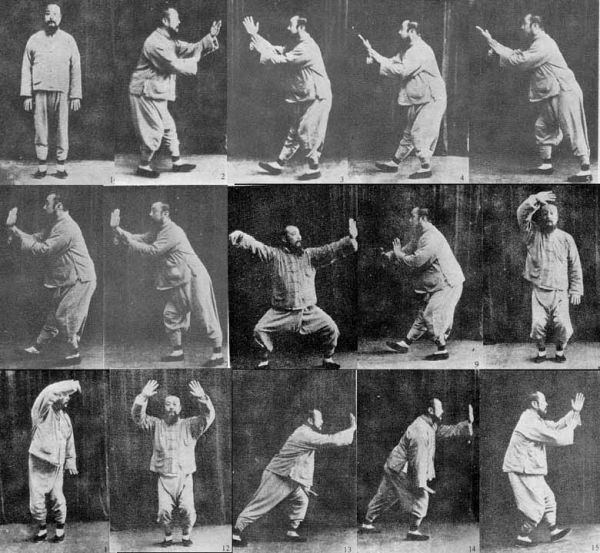

Pole Training in Push Hands

1️⃣ What Two Poles Between Two People Actually Do

Instead of palm-to-palm contact,

the poles create:

It removes:

Now everything must come from:

Center → Kua → Legs → Ground.

2️⃣ Typical Structure Position

Usually:

Each person holds two short poles

Right hand to right hand pole

Left hand to left hand pole

Poles cross slightly forward

Arms remain rounded (Peng structure).

Elbows sunk.

Shoulders relaxed.

3️⃣ What This Trains in Push Hands

With palm contact, people can:

Adjust angles subtly

Collapse wrists

Press with fingers

With poles, you cannot.

The poles expose:

Two poles mean:

You cannot hide imbalance.

4️⃣ How to Receive With Two Poles

When partner pushes one pole more than the other:

Do NOT:

Do NOT:

Instead:

Let both pressures enter center.

Imagine:

Two arrows entering a rotating sphere.

The sphere does not tilt —

it rotates slightly to absorb.

5️⃣ Central Equilibrium Test

If your center is correct:

If incorrect:

One elbow flares

One shoulder rises

One knee collapses

Pelvis shifts laterally

Two poles are ruthless in revealing this.

6️⃣ Rebound with Two Poles

Very important:

You cannot rebound with one arm only.

Proper issuing is:

Ground → Both legs → Dantian rotation → Both poles expand simultaneously

Even if direction is diagonal,

the center remains unified.

If one side issues earlier,

your opponent will feel the split.

7️⃣ Why This Is Advanced Push-Hands Work

This method trains:

It is excellent preparation for:

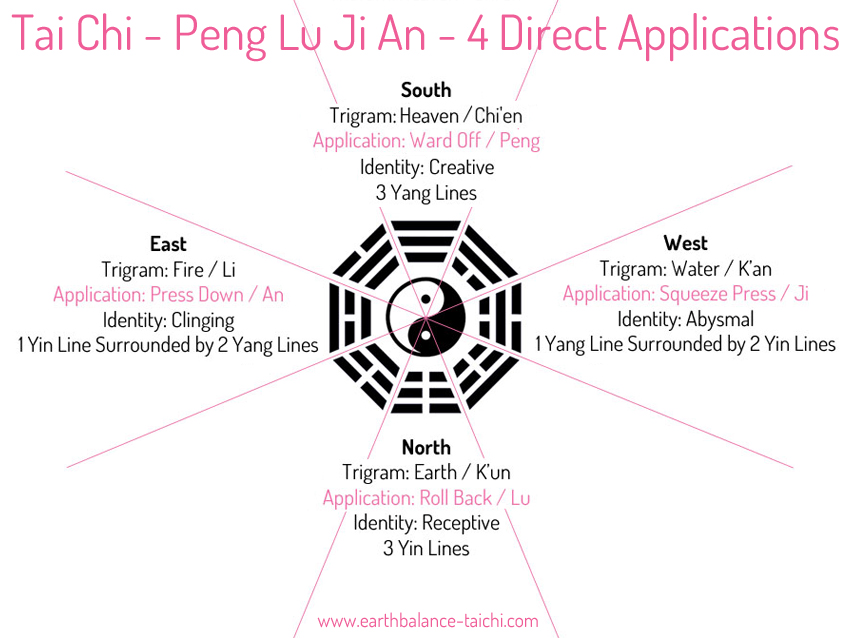

8️⃣ Theoretical Link to Classics

This directly expresses:

立身中正安舒

"Stand upright, centered, comfortable."

And:

上下相隨

"Upper and lower follow each other."

Without true center,

two poles immediately expose the weakness.

9️⃣ Advanced Internal Goal

At higher level:

You no longer feel two poles.

You feel one field.

Like:

Two tangent lines touching one sphere.

Both hands are merely extensions of the same core.

If you’d like, we can now explore:

• How stepping integrates into two-pole push hands

• How diagonal neutralization works with poles

• How this improves your designated push-hands competition model

• Or how Wu-Hao style might interpret this

Which direction shall we deepen?Trains🟤 Traditional Model: Tai Chi Long Pole (大杆 / 黏杆)

The long pole exaggerates three things:

Leverage magnification

Structural honesty

Central instability exposure

If your center deviates even slightly —

the pole tells the truth immediately.

2️⃣ Receive & Rebound — Mechanism Explained

You asked specifically:

How to learn receive and rebound and remain central equilibrium?

Let’s separate into phases.

Phase A — Receiving (接)

What NOT to Do

What Actually Happens

When force enters the pole:

1️⃣ Hands do not act first

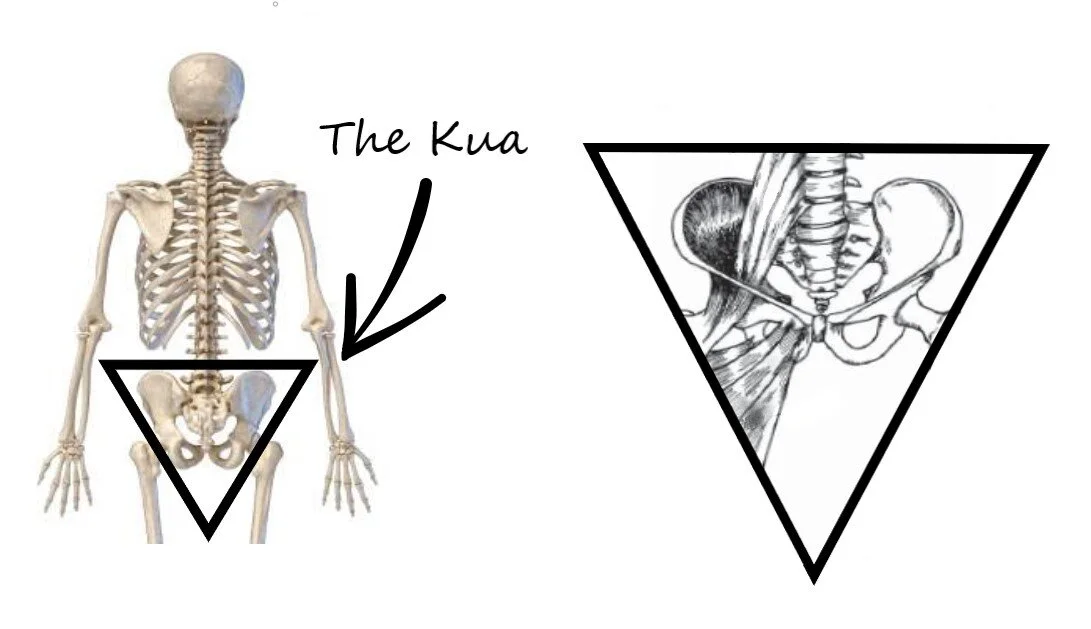

2️⃣ Force travels into kua (胯)

3️⃣ Weight spirals down to Yongquan

4️⃣ Ground reaction force builds

Biomechanics:

Shoulders relax → load transfers through fascia chains

Spine stays vertical

Kua folds microscopically

Pelvis remains level (not tucked aggressively)

This is suspension absorption, not muscular bracing.

Phase B — Storing (蓄)

The pole forces you to discover:

You cannot rebound if you did not fully receive.

Storing is:

Elastic lengthening of posterior chain

Spiral winding through dantian

Vertical pressure compression into floor

It is NOT:

Squatting

Muscle tightening

Locking knees

Phase C — Rebound (發)

Rebound in pole training teaches:

Power does not go from arms outward.

It rebounds from the floor upward.

Sequence:

Yongquan → ankle → knee → kua → dantian → spine → shoulder → elbow → wrist → pole

If central axis deviates,

rebound leaks sideways.

3️⃣ Remaining Central Equilibrium

This is the most difficult part.

Long pole magnifies imbalance because:

Correct Internal Model

Return to your sphere theory:

Feet = contact + rebound points

Kua = equator

Dantian = rotational core

During receiving:

If you tilt → you lose central equilibrium.

4️⃣ Two-Person Long Pole Methods

Method 1: Static Receiving Drill

Both hold pole.

One pushes slowly.

Receiver:

No stepping

No retreating hips

Allow downward spiral

Goal:

Feel pressure going to soles, not shoulders.

Method 2: Spiral Neutralization

Push is diagonal.

Receiver:

Do not "block".

Pole should feel like:

"Rolling apple on sphere surface"

Method 3: Sudden Pulse Test

Partner gives short shock.

Check:

Did shoulders rise?

Did chest collapse?

Did pelvis jerk?

If yes → center unstable.

5️⃣ Theoretical Foundations

Classical References

From Tai Chi Classics:

引進落空

"Lead into emptiness"

其根在腳

"The root is in the feet"

Long pole training literally forces these truths.

6️⃣ Common Mistakes in Long Pole Practice

| Mistake | What Happens |

|---|

| Leaning back | Lose vertical axis |

| Over-tucking tailbone | Pelvic lock |

| Arm resistance | Shoulders stiffen |

| Knee collapsing inward | Kua disconnected |

| Trying to rebound too early | No ground storage |

7️⃣ Physiological Explanation

Long pole trains:

It does NOT primarily train muscle power.

It trains force transmission efficiency.

8️⃣ Advanced Internal Goal

At higher level:

You do not feel:

You feel:

Continuous rolling pressure exchange.

Like two spheres contacting at a tangent point.

9️⃣ Ultimate Standard Test

If:

You can receive without shoulder movement

Rebound without visible preparation

Maintain vertical axis under sudden torque

Then central equilibrium is stabilized.

Excellent question.

Where you place the pole determines what structure is being trained — arm power, shoulder frame, kua transmission, or whole-body elasticity.

Let’s go progressively from beginner to advanced.

1️⃣ Most Common Contact Point — Forearms (Primary Method)

Why forearms?

Because they are:

This trains:

Peng structure through forearm arc

Relaxed shoulder suspension

Force entering through ulna line toward elbow

Key detail:

The pole rests on the meaty part of forearm, not wrist joint.

If wrist collapses → structure broken.

2️⃣ Mid-Level — Elbow Line (肘線)

Now the pole is closer to elbow.

Why?

To remove hand manipulation.

This reveals:

This is powerful for training central axis transmission.

If elbow drifts backward → you are resisting.

If elbow drops downward → kua disconnected.

3️⃣ Advanced — Kua Line / Lower Abdomen Alignment

This is not literally pressing the pole into your stomach.

It means:

The pole aligns with:

Forearm → elbow → shoulder → kua → opposite leg.

In high-level practice, the feeling is:

The pole is touching your center, even though physically it rests on the arms.

Now the body behaves as one elastic unit.

4️⃣ What You Should NOT Do

Avoid placing pole:

Directly on chest (collapses structure)

On wrist joint (too weak)

On shoulder (too high, lifts center)

Against stomach (no external frame support)

Unless doing specialized drills.

5️⃣ In Two-Person Drills — Typical Configurations

Parallel Push (Front-Facing)

Pole usually rests on:

Diagonal Neutralization

Pole rests:

Testing Root

Sometimes pole touches:

6️⃣ Internal Principle (More Important Than Location)

The real question is not:

Where is the pole touching?

But:

Where does the force go?

Correct pathway:

Pole → forearm → elbow → shoulder socket (relaxed) → spine → dantian → kua → leg → foot → ground

If it stops at shoulder → you are using upper body.

If it stops at knee → structure collapsed.

If it reaches foot → you can rebound.

7️⃣ For Your Level (Given Your Sphere Model)

You should train mainly:

✔ Forearm contact

✔ Elbow-line receiving

✔ Diagonal spiral entry

Because you are already studying:

Dantian rotation

Central vertical axis

Rolling sphere model

Pole training becomes your external validator.

Ah — now you are describing 雙杆練習 (two-pole training).

That is a different level from single long-pole work.

When two poles are used — one for each hand —

the purpose is no longer just receiving force.

It becomes:

Training independent hand connection while maintaining one central axis.

Let’s clarify this carefully.

1️⃣ How Two-Pole Training Is Usually Positioned

Typical structure:

Each partner holds two short poles

Right hand connects to right hand

Left hand connects to left hand

The poles cross in front

So now:

You have two incoming force lines, not one.

This exposes whether:

Your center splits

Your shoulders separate

Your kua disconnects

2️⃣ Where Exactly Do They Put the Poles?

Usually:

✔ On the Palm / Laogong line

Not gripping tightly — but resting.

Why?

Because palm connection trains:

✔ Or Slightly Toward the Heel of the Palm

To avoid wrist collapse.

Very important:

The wrist must stay neutral.

If wrist bends, force stays in arms.

3️⃣ What Two Poles Are Actually Training

With one pole:

You learn whole-body transmission.

With two poles:

You learn bilateral integration.

Meaning:

Left and right arms must feel separate,

but center must feel single.

This directly trains:

This matches your “human sphere” model exactly.

4️⃣ The Big Problem Two Poles Reveal

Most practitioners:

Resist one pole

Yield on the other

Or shift weight unevenly

But correct method is:

Receive both poles into one center.

You do NOT:

Fight left separately

Fight right separately

Instead:

Both pressures spiral into the same dantian field.

5️⃣ How to Receive with Two Poles

When partner pushes:

1️⃣ Relax shoulders

2️⃣ Let elbows sink

3️⃣ Micro-fold kua

4️⃣ Feel pressure go to soles

Not:

Push back with right arm.

Pull back with left arm.

It must feel like:

Two ropes pulling a suspended bell.

The bell does not tilt —

it vibrates from the center.

6️⃣ How to Rebound with Two Poles

Rebound cannot be:

Right arm first, then left.

It must be:

Ground → center → spiral → both poles simultaneously.

Otherwise your body splits.

This is why two-pole training is very advanced.

7️⃣ Theoretical Explanation

This practice develops:

It prevents:

8️⃣ Classical Concept Behind It

This relates to:

左右相顧

“Left and right mutually attend.”

And

由中而發

“Issue from the center.”

Two poles make this impossible to fake.

9️⃣ For You (Given Your Research Depth)

Two-pole training is excellent for:

• Testing designated push-hands structural neutrality

• Refining diagonal issuing vs straight issuing

• Eliminating hidden shoulder tension

• Stabilizing central equilibrium under multi-vector load

If you'd like, I can next explain:

🔹 How two-pole training improves diagonal 掤捋擠按

🔹 Or the biomechanics of how the dantian rotates without tilting

🔹 Or how this relates to Wu-Hao spiral stepping theory

Which direction shall we go?