Daniel Sherrer's Post

https://www.facebook.com/groups/learningtaichi/posts/950370760380406/

I used ChatGPT to analyze Tai Chi. This post contains the scientific analysis I asked it to perform as well as the initially analysis of concepts. (The original analysis is below the scientific)

--SCIENTIFIC ANALYSIS--

1. Song (Relaxed Structure)

Physics (Biomechanics):

"Relaxed structure" in physics aligns with the principle of minimal mechanical resistance. The body operates closer to a neutral tension state where force can pass through joints without significant frictional losses. Think of this as creating low-viscosity低粘度 transmission channels for mechanical energy.

Kinesiology:

This involves selective inhibition of tonic muscle contraction, especially in superficial muscles. The Golgi tendon organs and muscle spindle feedback loops allow proprioceptive systems to downregulate excessive tension. This increases sensorimotor sensitivity, allowing reactive adaptation via reflex arcs and cortical modulation.

歌利氏肌腱器,是肌腱里的一种感觉受体,能察觉张力,提醒大脑放松肌肉,以防过度拉伤。

2. Peng (Expansive Force)

Physics:

Peng is an omnidirectional vector field — an internal pressure system where the body creates elastic preloading similar to tensegrity structures. The limbs behave like inflated tubes resisting deformation, dispersing incoming vectors across a spherical or cylindrical frame.

Kinesiology:

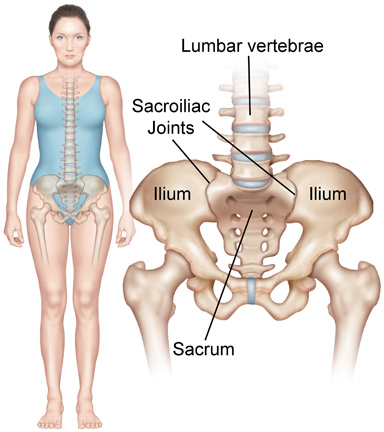

This is achieved by myofascial pre-activation—a coordinated isometric co-contraction of agonist-antagonist pairs (e.g., deltoid vs. latissimus). This expands the biotensegrity matrix, especially across the thoracolumbar fascia, scapular sling, and pelvic girdle, enhancing structural integrity under load.

Physics:

Rooting creates a ground reaction force (GRF) countervector, enabling Newton’s 3rd Law expression: for every action, an equal and opposite reaction. Rooting optimizes center of mass (COM) alignment over the base of support (BOS), increasing stability and allowing efficient force redirection.

Kinesiology:

This activates deep postural muscles (e.g., transversus abdominis, pelvic floor, gluteus medius) to maintain a stable kinetic base. Proprioceptive mapping through Meissner and Pacinian corpuscles in the plantar fascia help refine rooting feedback in real time.

Physics:

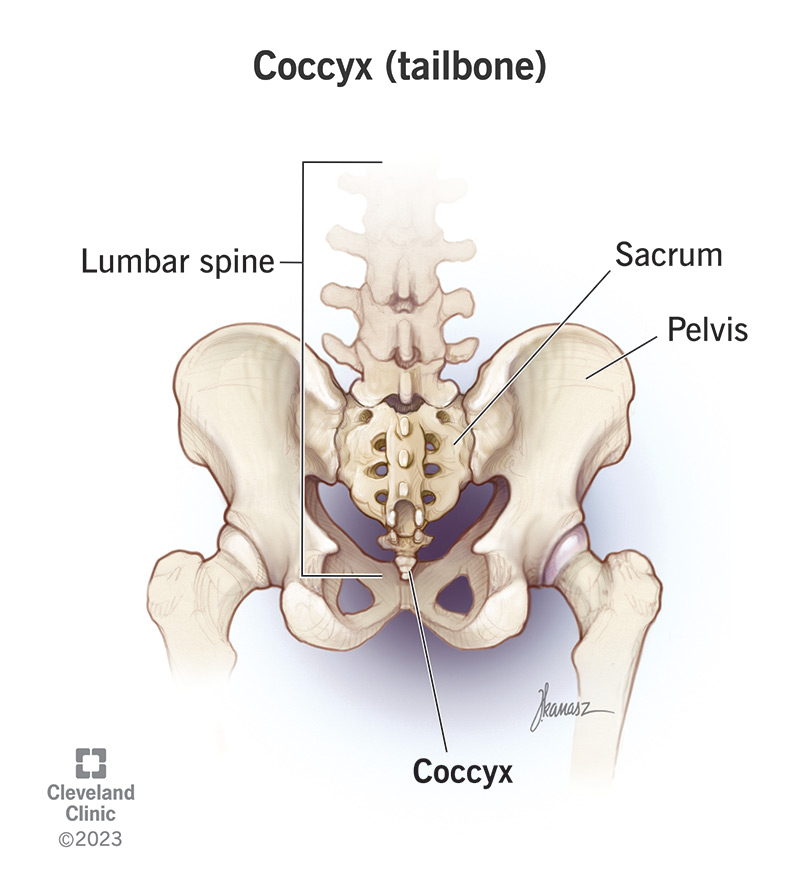

Spinal alignment creates a central load-bearing axis, minimizing moment arms on each vertebral joint. By reducing torque deviation, it prevents shear stress and enables efficient torque transmission during rotational or linear movements.

Kinesiology:

The multifidus and erector spinae coordinate with the deep cervical flexors and psoas to keep the spine stacked. Neurologically, proprioceptive feedback from muscle spindles in intervertebral muscles helps maintain alignment through micro-adjustments.

5. Dan Tian-Centered Movement

Physics:

The Dan Tian acts as a rotational inertia center akin to the center of mass in a gyroscope. Movement initiated here produces less angular momentum distortion across distal limbs, thus centralizing torque production.

Kinesiology:

Requires core muscle recruitment (TVA, IO, EO, rectus) with motor engrams that initiate motion from the abdominal-pelvic region. The somatosensory cortex and supplementary motor area (SMA) are engaged for precise coordination, particularly for motor sequencing.

6. Whole-Body Coordination (Unification)

Physics:

This is an example of closed-chain kinetic energy transfer. Each joint acts as a node in a mechanical wave propagator, where impulse and momentum travel through linked segmental rotation (like a whip or snake motion).

Kinesiology:

The neuromuscular system uses intermuscular coordination patterns stored in the motor cortex and basal ganglia. Synchronization of muscle firing is mediated through feedforward loops and central pattern generators (CPGs).

7. Weight Differentiation (Empty vs. Full Leg)

Physics:

This utilizes center-of-mass displacement strategies to maintain dynamic equilibrium. By shifting the COM laterally or sagittally, the full leg serves as the reaction base, and the empty leg acts as a kinematic initiator for locomotion or evasion.

Kinesiology:

Controlled by hip abductors/adductors and ankle stabilizers, this differentiation demands high proprioceptive acuity and afferent feedback from the vestibular and somatosensory systems to maintain spatial awareness during transitions.

8. Silk-Reeling Mechanics (Chan Si Jin)

Physics:

This is the generation of helical torque vectors via coordinated angular momentum across multiple axes. A rotational system where torque is conserved and stored kinetic energy is efficiently released through the “coil-uncoil” paradigm.

Kinesiology:

Primarily uses spiral myofascial chains (per Thomas Myers’ Anatomy Trains), such as the spiral line and functional lines. It creates continuous tension and rebound through the serratus anterior, internal obliques, and scapular stabilizers.

9. Kua (Hip Crease) Flexibility

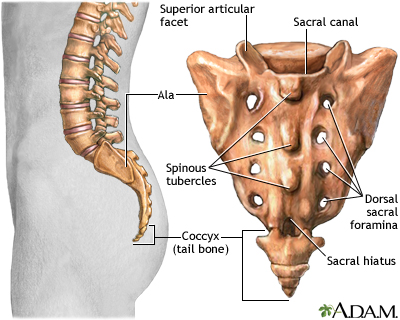

Physics:

The kua acts as a ball-and-socket energy junction. Proper flexion and rotation reduce translational resistance, allowing kinetic energy to pass unimpeded between torso and legs. It is the pivot point for rotational inertia control.

Kinesiology:

Requires flexibility and neuromuscular control of iliopsoas, piriformis, gluteus maximus, and tensor fascia latae. Dynamic kua control also involves active inhibition of hip stabilizers during transition phases to prevent locking or impingement.

10. Sinking and Rising (Vertical Force Management)

Physics:

These are vertical potential energy exchanges. Sinking lowers the COM, increasing gravitational stability, while rising leverages stored elastic energy (via tendons/fascia) into upward motion — like loading and releasing a spring.

Kinesiology:

Involves eccentric-concentric cycles in quadriceps, hamstrings, gastrocnemius, soleus, and pelvic floor muscles. Controlled breathing patterns often synchronize intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) with vertical movement for spinal support and energetic continuity.

11. Kinetic Chain Activation

Physics:

This reflects sequential impulse generation and transmission through the proximal-to-distal principle. Each joint transmits motion like a gear in a clock, where the timing of release is critical to constructive energy summation.

Kinesiology:

Involves temporal recruitment of muscle groups with precise timing. Pre-activation potentiation and reciprocal inhibition help fire correct sequences. Motor learning centers (cerebellum, basal ganglia) refine this kinetic choreography.

Physics:

This is the conversion of strain energy to kinetic energy using viscoelastic tissue properties. Fascia acts like a non-linear spring — the more you stretch it (within limit), the more rebound energy is stored and released.

Kinesiology:

Involves loading the myofascial web under tension and releasing it via stored elastic potential. Titin molecules, epimysial tissue, and collagenous networks play key roles. Efficient Jin use avoids muscle fatigue and maximizes recoil speed.

13. Fajin (Explosive Release of Force)

Physics:

Fajin is the superimposition of momentum and acceleration, achieved by summating stored elastic force, gravity, torque, and muscular impulse into a singular, short-duration impulse. It's the Tai Chi equivalent of a ballistic force vector.

Kinesiology:

It involves preloading via coiling (Silk-Reeling) followed by rapid neural activation of Type IIb (fast-twitch) muscle fibers. The stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) and rate of force development (RFD) are maximized through precise neuromuscular timing and spinal reflex arcs.

1. Song (Relaxed Structure)

Definition: Song means to relax the muscles and joints without losing structural integrity. It’s not limpness but a state of tension release.

Why important: Tension blocks energy flow and wastes effort. Song enables smooth, efficient motion, better sensitivity, and reduces injury risk.

Relax the superficial muscles but maintain core stability.

Avoid gripping or bracing; instead, use connective tissue and skeletal alignment for support.

Example: When pushing, muscles “yield” slightly rather than harden, allowing power to flow through without resistance.

2. Peng (Expansive Force)

Definition: Peng is an outward, buoyant force within the structure, like gently inflating an internal balloon. It creates a resilient frame that can resist and redirect force.

Why important: Peng forms the foundation of Tai Chi’s defensive and offensive abilities by maintaining shape under pressure.

Maintain slight outward pressure in limbs and torso.

It’s a dynamic force — always present, neither too stiff nor too soft.

Example: When someone pushes you, your arm maintains Peng by “pushing back” structurally without muscular strain.

Definition: Rooting is the connection and force transfer from the feet to the ground, creating stability and balance.

Why important: Without rooting, movements become unstable and inefficient; power can’t be grounded or transmitted properly.

Distribute weight evenly through the foot’s surface (heel, ball, toes).

Relax legs to absorb and adapt rather than stiffen.

Use the ground reaction force to push or resist without losing balance.

Example: Standing firmly during a technique so that you don’t get pushed over easily.

Definition: Keeping the spine vertically aligned but naturally curved, acting as the central axis for all movement.

Why important: Proper alignment optimizes balance, facilitates rotational power, and prevents injury.

Head stacked over the spine, shoulders relaxed but not slouched.

Spine maintains natural curves, allowing flexibility and strength.

The spine rotates smoothly during movement without collapsing or overextending.

Example: Turning the waist in a Tai Chi posture while keeping the spine upright.

5. Dan Tian-Centered Movement

Definition: Movement originates from the Dan Tian, the lower abdomen area (~3 inches below the navel), which is the body's energetic and physical center.

Why important: Using the Dan Tian as a movement source integrates upper and lower body for power and coordination.

Engage the core muscles lightly around the Dan Tian.

Lead motions from this center rather than the limbs alone.

Helps unify breath, intention, and movement.

Example: When stepping or turning, the hips and torso rotate initiated from the Dan Tian.

6. Whole-Body Coordination (Unification)

Definition: All body parts move as a connected, coordinated unit rather than isolated segments.

Why important: Enables smooth, efficient, powerful, and balanced movements. Prevents wasted energy and disjointed motion.

Feet, legs, hips, spine, shoulders, arms, and hands work in harmony.

Movements flow seamlessly from one part to another.

Example: When throwing a punch, the power flows from the feet through the legs, waist, torso, and finally the fist.

7. Weight Differentiation (Empty vs. Full Leg)

Definition: Clear distinction between the leg bearing the body's weight (full) and the leg free or lighter (empty).

Why important: Enables smooth weight shifts, balance, and mobility in stances and steps.

The full leg is firmly grounded and stable.

The empty leg is relaxed and ready to move.

Weight shifts are deliberate and controlled, never abrupt or uncontrolled.

Example: In a step forward, the back leg becomes empty as weight transfers to the front leg (full).

8. Silk-Reeling Mechanics (Chan Si Jin)

Definition: Continuous, spiraling, coiling movements starting from the waist, expressed through limbs as internal rotational force.

Why important: Generates internal power, improves joint mobility, and connects the body into one unified system.

Waist leads rotation; limbs follow with twisting and untwisting patterns.

Spirals store and release energy, much like winding a spring.

Encourages relaxed muscles and elastic connective tissues.

Example: Circular arm movements that twist in one direction then unwind smoothly.

9. Kua (Hip Crease) Flexibility

Definition: Flexibility and controlled opening/closing of the hip crease area, essential for rooted steps and power generation.

Why important: Proper kua movement allows hip rotation, leg extension, and maintains connection with the ground.

Kua opens to allow stepping and twisting without tension.

Kua closes to stabilize and root the stance.

Example: Bending knees with hips slightly outward to prepare for rooted movement.

10. Sinking and Rising (Vertical Force Management)

Definition: Controlled vertical movement of the body’s center of gravity—sinking down to ground power, rising without tension.

Why important: Maintains balance and power; avoids collapse or unnecessary stiffness.

Sinking is a subtle dropping of weight into the legs and feet while keeping the spine upright.

Rising is a lifting motion that does not involve raising the shoulders or locking joints.

Example: Lowering into a stance smoothly then rising without losing structure.

11. Kinetic Chain Activation

Definition: Sequential and connected activation of body segments for power transmission: ground → legs → waist → torso → arms → hands.

Why important: Maximizes force generation and efficiency by using the whole body rather than isolated muscles.

Energy builds from the ground up through coordinated muscle activation.

Each segment links to the next like a chain, reducing energy loss.

Example: Power from a push starts in the feet and legs, flows through the waist and torso, and ends in the pushing hand.

Definition: Utilizing the elasticity of tendons, ligaments, and fascia to store and release energy, rather than relying solely on muscle contraction.

Why important: Provides explosive power with minimal energy expenditure and reduces fatigue.

Movements load connective tissues like a spring being compressed or stretched.

When released, stored energy adds speed and force to the motion.

Example: Twisting the torso stretches fascia, which rebounds to add power to a strike.

13. Fajin (Explosive Release of Force)

Definition: Sudden, focused burst of power generated by coordinated whole-body tension and relaxation, often following spiral mechanics.

Why important: Enables effective, instantaneous delivery of power in applications like strikes or pushes.

The body stores energy through relaxed tension and spiral coiling.

A rapid, coordinated contraction releases this energy in a single explosive movement.

Proper alignment and rooting channel the force efficiently.

Example: A sudden, whip-like strike that uses the entire body’s momentum and elastic recoil.